spikemagazine.com

[This article appears online at http://www.spikemagazine.com/1104noretreat.php%5D

November 2004

Street Fighting Men

Ben Granger talks to Dave Hann and Steve Tilzey, authors of “No Retreat”, a punchy account of their days fighting neo-Nazis in North-West England.

Back in the late 70s Manchester was a stronghold of Britain’s premier far-right party, the National Front. As factories and communities went down they went up, recruiting at pubs and football matches, bolstered by a backdrop of fear, poverty, ignorance and desperation. They strutted through the town’s grey streets by day, cudgelling random blacks and gays in dark alleys at night. Kicking around and insulting lefty paper sellers was another hobby. That was until a few young working-class activists, centred initially round the Socialist Workers Party and the Anti-Nazi League, decided to fight back.

“The Squads” -as they became known- eschewed the standard British lefty tactics. They didn’t depend on banners, slogans and face-painting. Men who could handle themselves, they responded to the NF in kind; with boots and fists. “The fash” weren’t used to people fighting back and before long it was they who were on the defensive.

As the NF dissolved into the more openly Nazi British Movement and other warring factions, Anti-Fascist Action grew from the ashes of the Squads, shunned and denounced by the middle-class leadership of the SWP, they still booted the Nazis out of central Manchester and took the fight further out, to the further reaches of the north-west and the country beyond.

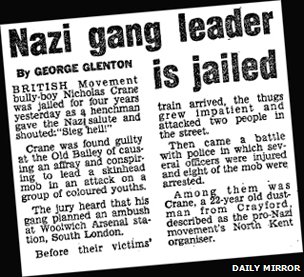

No Retreat is a memoir from two veterans of these struggles. While overlapping strongly, the first half is Squad member Tilzey’s story from the late 70s to mid 80s, detailing the collapse of the NF and the rise and fall of the psychopathic British Movement. AFA founder member Hann takes over from the 80s to the late 90s, recounting the fight against the new British National Party and their partners in thuggery Combat 18. It describes the movement’s very real successes, but also tells of the setbacks and the infighting endemic to groups of the left.

To say it doesn’t shy from the violent side of the struggle is an understatement. Fastpaced accounts of kickings and hammerings dominate the narrative. Dave jokes at one point that AFA considered seeking sponsorship from Lucozade for the use they made of their old style glass bottles “an ideal hand to hand or throwing weapon, and the police can’t arrest you for it as long as its still got som drink left in it.” Liberals and pacifists won’t be perusing this over their chiantis.

There’s a lot of knockabout humour too. At one point during a battle in London, Steve McFadden (Eastenders’ Phil Mitchell) is caught up in the scene; at another Dave and the AFA boys receive notice of a large gathering of Nazi boneheads in Manchester that turns out to be a scene for Robbie Coltrane’s “Cracker”.

It’s a lively, irreverent, thrills but no-frills account which at times reads like one of the numerous soccer-hoolie memoirs proliferating in the “True Crime” section at book-stores (and indeed its publisher Milo purveys many such books themselves). But amidst all the scrapping and joking is the constant and powerful message that fascism thrives when the workingclass is ignored and betrayed. The authors argue this betrayal has come not only from all the major parties, but from the middle-class leadership of far-left groups too, pursuing students with single issue politics rather than working people.

I met up with Dave Hann and Steve Tilzey for drinks on Deansgate in Manchester. The chain pub we meet in is corporate, with cosmetic concessions to local surroundings. By contrast, these two are the real deal. Older and broader now, they’re still imposing enough to intimidate the frailer sections of the master race. Steve is garrulous, warm, humorous and infectiously friendly, a quick-tongued and foul-mouthed Manc through and through. Dave is more soft-spoken and considered and wry, with a cosmopolitan accent reflecting his changes in location despite a longstanding base in Manchester. Both have retired from their street fighting roles, Steve works in local government, Dave is a plasterer. But their deep-seated resolve against the forces of fascism still burns bright.

What made you decide to release this book when you did?

ST: There were lots of people who did a lot of work for anti-fascism back in the previous decades, and their contributions haven’t been properly documented before. There was a fear they would be lost to history. Our book is a way of keeping the story alive.

You both got involved in far-left activist politics as very young working-class men in the 70’s and 80’s. Why is that less common these days, and why are groups like the SWP now largely middle-class?

ST: Basically, people like we were are less easy to control. Students are less bother, they do as they’re told.

DH: Getting out into work-places, where it counts, is a lot harder to do. It’s a lot easier to stick on campuses and bang on about single-issues. It just doesn’t achieve much. The most frequent response to your activities on the left and in the mainstream is that it’s “counterproductive” and that “you’re as bad as them”.

ST: Obviously, we get that all the time. It may seem simplistic to say that these are some seriously evil bastards and we’re the good guys…What I always say to these people is “what would you have done in the second world war”? That was a war against Nazis, and so was this. And it worked.

The book provides ammunition for your critics in detailing how you fought alongside questionable allies on the streets at times. Criminals with Irish backgrounds, Celtic football hooligans, Moss Side hard-men. And weren’t some people up for a fight with whoever?

ST: A lot of people you work with you won’t be in agreement with. I’ve stood next to many people in my time against the fascists. I’ve looked around and thought; these may not be people I’ve got much in common with, but we’ve all got one enemy. Anti-fascism is a broad church, and if people want to fight them it’s not up to us to turn them away because we disagree with them on certain issues.

DH: You’ve got to ask yourself, where do political activists come from? They don’t come fully formed into your ranks. Some people may just join in for an afternoon’s fighting sure, but its then you can try to persuade them. You should engage people like that, not ignore them.

It worked in ways other left-wing groups didn’t. We’ve had ex-NF members who’ve joined. We’ve had lots of football hooligans. Some of them just started out from the standpoint that they didn’t like way the NF and the BNP were bullying people around on the terraces. Then, when they talked to us, some got thinking about things in a more socialist-orientated way.

If someone got on to the coach with us with a copy of the News Of The World we’d welcome him. Other left groups would just be horrified and turn their noses up. We’d welcome him, and tell him why his paper was full of shit later. People are bombarded with right-wing propaganda throughout their lives. If someone’s got baggage, that’s fine, we weren’t gonna turn them away.

How do you feel that because of the violent nature of the book it’s often placed in the “true crime” section of bookshops?

ST: I’ve heard its been placed in the comedy sections at times myself. [laughs] I know people have labelled this book another soccer book. The book talks about violence but it details how it was. It wasn’t pleasant at times, we were scared, of being arrested, of being kicked in. But at the end of the day, when these people are in your town, you’ve got to take action. You’ve got an obligation.

The Squads and AFA weren’t just about generals running round, we were all equal with different qualities, good fighters, good communicators, spotters, good drivers even, they all had a part to play. When people say “its like a football book” I can understand that, but I think it comes over that it wasn’t the same, this wasn’t just a load of blokes saying “what a good row” after a punch up. If me and Dave had wanted to just be football hooligans then we would. It would have been a lot easier. And we didn’t.

DH: At then end of the day, we wanted people to read this book. AFA campaigned, we worked in communities, we did talks in schools, we did mass leafleting. We could have concentrated on all that and no-one would have read it. I challenge anybody to write a book like that and have it widely distributed. Yes there was a lot of violence, and yes the book talks about that. But you can walk down Manchester today with a banner of Lenin and no-one will touch you. That’s a result.

The ultimate vindication of the AFA strategy seems to be that very thing. Even now, with the BNP in a huge resurgence, there are seemingly no go areas for them: most of Manchester (as opposed to Greater Manchester), South Yorkshire, even a lot of East London. Prime, poor areas for BNP recruitment but they don’t seem to try it now. And these were the areas where AFA was most active…

DH: Absolutely. Where we were strongest they are weakest now. Basically, we took out a generation. These are people who thrive on ruling the streets, inspiring youngsters to look up to them. We took the role-models out for kids like that. Even today in Manchester, with the BNP riding high nationally, you don’t see them Manchester, yo don’t see paper sellers, you don’t see stickers. Not even graffiti.

But you certainly can’t be complacent even here. I’ve often likened fighting fascism to nailing jelly to the ceiling.

ST: So speaks a true dodgy plasterer..

DH: Yes, they always take the piss..But the point is you can never stop. And neither will they. There’s a line of argument that says fascism will always be there as long as capitalism is. It’s probably true. But do you wait for capitalism to dissolve when there’s a gang attacking an Asian shop? You have to do something at the time and that’s what we did.

As you detail in the book, there’s your own strongholds you’ve secured, but there’s other places like Burnley where you fought them off but now they’ve taken hold. As you said, you kicked them out, but there’s a vacuum in isolated working-class places like that which no-one filled and they came back. Would a change in the Labour government change things?

ST: No way.

DH: Not one iota. We were saying back in the 70’s Labour had lost it, lost touch with working people. How much worse is it now? They’ve got their heads completely up their arses and there’s no way back. They’re trying to copy the situation of the Republicans and the Democrats in the US.

Except now Labour are closer to the Republicans!

DH: Well, yeah….[laughs]

So do you see anyone as voicing a true working-class alternative?

DH: Well there are a few, there’s anarchist groups emerging which seem to have the right idea…

ST: People say, why would you hang around a bunch of revolutionary groups when it just ain’t gonna fucking happen? To be honest I go along a lot more with that view now. Let’s face it, the state is the biggest gang in town. It’s got the biggest mob. If it wanted to it could wipe out the left just like that like in Chile. I can’t really see the point in things like the SWP any more. You could say that’s me getting old, that’s me in the comfort zone now, with me season ticket for OT (Old Trafford). But you do still need to campaign on individual issues. There’s nothing to be gained from the SWP, there’s gonna be no great change…watch this fucker disagree with me…

DH: I do think society can change more but I agree you’ve got to campaign on people’s lives. If you can go to a housing estate and get the lifts working in a tower block, people remember who you are. Campaign on these issues, get things done, and when the fascists walk down your street they listen. Sometimes we were so busy fighting the fascists we didn’t spend too much time offering alternatives. You’ve got to do both. Take people’s hearts and minds away from them and offer them an alternative.

Over the last twenty to thirty years the left has moved further and further away from the working-class. If this doesn’t change it’s a historic mistake we’re going to live to regret. The book details the more subtle, undercover work that you did in particular Steve, at first for the Squads and later for [anti-fascist magazine] Searchlight. This included spying, secret photography, bugging meetings. You come over as being particularly enthusiastic about this line of work.

ST: Yes well it goes back to when I was young that, I’d always fancied myself as a bit of a James Bond.[laughs].No I’ve always liked codes, things like that.

In particular when I got involved with Searchlight I met people who really new their stuff with surveillance. As well as bugging meetings we did the bins of a lot of leading people on the far-right, John Tyndall, Martin Webster, Lady Birdwood. Some of that stuff made it into the book, some didn’t. I’ve still got a lot of shit on these people that’s not yet been made public.

What did you make of the recent BBC undercover documentary on the BNP?

ST: I thought it was well-done, it was a good mainstream documentary. Of course, it told us nothing we didn’t know about these people ourselves. We’ve bugged BNP meetings where the stuff they were saying puts that right in the shade.

One thing that comes over very strong in the book is that you’re Reds in both senses of the word. By your account Manchester United was always heavily anti-fascist in character, yet Manchester City was far more of a hotbed of NF support. Why is that?

ST: There really is no clear answer to that. Historically there was the old United-Catholic

City-Protestant thing, and I think there’s an element of that.

And yet City actually have more black fans than United too…

ST: I know; it’s weird. I do think a lot of it is just down to coincidence and can’t be explained. Groups of lads coming from certain areas, hanging around together, supporting the same team. Some just supported the same politics too, including far-right politics.

It’s not clear cut at all. I’ve certainly heard a fair amount of racist shite at United over the years, we just always managed to isolate them. We helped do that through fanzines we wrote for a while. It was honest, 90% football and 10% politics but it worked. At the same time, City has had its anti-Nazis who’ve given us support.

One more thing is that City has always been a big England supporting team and United hasn’t, once again because of Irish ancestry.

How do you feel about the whole issue of supporting the national team, and indeed patriotism in general?

ST: I want England to win. I’ve got Irish roots but I don’t do the plastic paddy thing like others. I was born in England, I want them to win, I’ll watch the football and I’ll cheer if they score.

Do you see the current popularity of the flag of St George as a good thing?

ST: Look at [Bolton boxer] Amir Khan. He seems to be really into it as are loads of other normal people at the moment and I think that’s good and positive.

DH: Anything that reclaims it from these morons is a good thing.

Do you think the blanket-rejection of all patriotism by much of the left has led to its lack of popularity amongst the working-class?

ST: Definitely. Just being anti-British is pointless and negative. Because of the BNP and NF fucking around with it I admit to thinking twice whenever I see the Union Flag or the Flag of St George, but I shouldn’t have to. The Irish get together, have a great time, celebrate their team –

DH: Yes but they don’t have a history of oppressing other people so its not quite the same.

ST: I know. It might sound naïve but I still think you can reclaim that. This country has got a lot of real proud history, Its union movement, the Tolpuddle martyrs, the fight for democracy. It ‘s not just about kings, queens and the empire. We shouldn’t let the rightwing hijack it.

It must be sickening to see the BNP’s current electoral success…

ST: It’s extremely scary the gains they’re making. They’re capitalising on Islam and the Iraq war. It’s ringing a lot of fucking bells in your Burnleys, your Blackburns. We’ve got difficult times ahead. The worse it gets in Iraq and the middle-east, they worse it’ll get here. Fair play to the anti-war movement, they need to be out there making the point this isn’t an issue the enemy should be winning on.

DH: The thing is, we kicked them out of certain zones, and we largely scared them off the streets altogether. But now they’re trying to follow Le Pen in going for full-on electoral respectability and doing well. The fact that they don’t have a such a big street presence has put anti-fascism into a state of flux.

ST: Except they still are on the streets. Not at day but at night, they’re going into pubs, stirring up trouble. They’re just not out on marches behind rows of police any more, and it makes it harder to deal with them.

[BNP Leader] Nick Griffin is modelling himself on Le Pen, in having a respectable electoral platform, but also in the sense of having a hardcore of activists still there ready to intimidate the enemy. The core of the BNP hasn’t changed at all. Combat 18 are often portrayed in the media as deadly organised Nazi terrorists, yet in your accounts of fighting them Dave you describe them as the exactly the same gangs of misfits and football hooligans you fought

under the different banners of the NF and BNP. Were they really no more of a threat?

DH: Well for a start the British Movement would have eaten them alive. They had a lot more capability to cause serious damage.

Yes C18 had dangerous psychos but they were also full of wind. They took credit for things they didn’t do.

But did they not send you a letter bomb at one point?

DH: The one really serious move C18 made was getting Scandinavian allies to send bombs to the AFA office, and to Sharon Davies for having a black husband. In general they attacked more right-wingers than left-wingers. C18 was a trap, a state-run set up.

Really?

DH: Charlie Sargent, one of the leaders, was in the pay of the state. He talked up a lot, attracting the most dangerous elements, but then just ended up attacking and killing Nazi rivals.

ST: Charlie’s inside for killing [C18 rival] Chris Castle. Now his brother Steve Sargent and Will Browning’s lot are at each other’s throats. To say C18 didn’t achieve much is an understatement, which makes you think doesn’t it? MI5 were interested in the links between British Nazis and Loyalist terrorists, who muck around a lot together. So C18 was set up by MI5 as a honey-trap for Loyalists that got out of hand. There’s a lot of mistrust and subterfuge amongst both the far-right and

their opposition. Steve, you’ve worked with Searchlight, but AFA members have denounced Searchlight for working with MI5 themselves.

ST: With these sorts of politics, there’s a lot of intrigue. I’ve said how I enjoyed doing the bins more than smacking heads together, but if we’re doing that, don’t think the state isn’t doing it, for fuck’s sake.

There has been a relationship between Searchlight and the secret services yes. At times people’s lives have been saved in foiling bombs, so I think it’s a pay-off that’s sometimes been justified. At times maybe it got too cosy, and I can understand why people see that. Some ex-AFA have asked Dave how he could even work with me on this book, y’know, as I’m “tainted” by the magazine…

DH: If you think Searchlight is a state-run organisation, fair enough, gather your own intelligence. I don’t have any truck with Searchlight myself. I think it’s been involved in underhand things. But I would say grow up and don’t blame it for everything that ever goes wrong. They are what they are, we are what we are, let’s just all do what we do.

What final message would you like this book to have?

DH: What’s been nice to see is as sales have fallen in this country, its started to sell elsewhere, all over the place, in France, the Czech republic, the US, Germany.

ST: We’re not setting ourselves up as the authorities on anti-fascism. We’re far from “the experts”. All we’ve done is been honest and tell it how it is. I was a bit neurotic about

when this came out, but after my kid being born its actually the proudest thing I’ve ever done. You know what… the best thing is there’s the sons of friends; young kids, and they read it and it gives them inspiration. They say it’s got energy to it.

DH: I know a Celtic fan who works on a building site, and he told me this book gave him the confidence to stand up to the racist dick-heads he works with. He said he reads a little

bit each day and that gives him a bit of fight to stand up for himself against them. Other people did this for longer than we did, and did more than we did. I welcome other books about the subject. I’d like everyone to tell their own stories and keep these things alive. There’s even talk of a film being made of it, which may or may not happen.

ST: Yeah there’s rumblings, a Ken Loach style thing. Phil Mitchell would obviously play Dave-

DH: Yeah and the guy who plays Curly Watts can be you Steve!

[For the record there are slight echoes, though Dave is slimmer than Mr MacFadden and Steve’s resemblance to Kevin Kennedy is of the nose only.] Steve, from your recounts of some of your NF opponents in the book you seem to know some of them. And when you were in Strangeways, [Steve and other Squad members received several months’ imprisonment for intimidation of an NF skinhead in what Steve considers was a possible MI5 set up] they put you in a cell with Kev Turner, an north eastern NF organiser. Did these experiences give you a grudging respect for some of them?

ST: When I was banged up with Kev Turner I said to him “I know what you’re in for, you know what I’m in for, and we both know why they’ve put us in together. Are we gonna go down that road?” We co-operated for the duration. He seemed alright for a time, and I thought, “Is he really that bad?” I thought they might be some hope for him. I thought I may get through to him. But basically he was a coward. He was a Geordie in with a bunch of Mancs and just kept his head down. He showed his true colours when he got out before me and sent me a postcard from Auschwitz. “Having a great time Steve!” He was a snake; not a pleasant feller.

As for the others, yeah, I know some of them, we’ve spoken. One of the people I mention in the book has done a complete sea-change now and hands out anti-racist leaflets. But people like Kev won’t change.

DH: A lot of fascists and Nazis are in it just for the row. Nine times out of ten these people will crack. I think you could convince 90% of fascists of the error of their ways, if you had enough time. Some, the hardcore, I don’t think you could ever change them short of killing them. Which by the way is a route we’ve never gone down. We value our liberty as much as anyone. Nick Griffin has described this book as a manual for violent action against nationalists. I think he’s shot himself in the foot saying that – Well he’s already shot himself in the eye! [laughter.] [Griffin has indeed got a glass eye due to a self inflicted gunshot wound during far-right survivalist manoeuvres]

ST: I wonder if he did that to follow Le Pen who’s also got one eye.

DH: And of course Hitler only had one ball!

ST: Singles all round lads…I think what Dave means is if we’ve inspired people we’ve done our job.

***

There are many who would still denounce Steve and Dave as a pair of thugs backing it up with political pretensions. That certainly isn’t the impression I went away with. The liberal argument of “don’t sink to their level” completely ignores the very real and appalling violence meted out by the far-right against completely innocent blacks, Asians and gays. If the police are slow to defend them, as has often been the case, taking direct action is not self-indulgent violence but an urgent necessity. To compare Steve and Dave to the vicious bullies they were up against; sadists, firebombers, desecrators of cemeteries, and murderers, seems the worst kind of prissy-minded pacifism.

Meeting Steve and Dave I was struck by their essential decency and normality; regular lads who took the decision to stand up to a great evil in the ways they knew how. At the same time there was something about their inquisitive nature, their background travelling that quite definitely puts them apart from the mass of the defeated and impressionable they have spent much of their lives trying to convert or confront.

As I left them I was invigorated by their spirit of defiance, yet despondent that a newer generation don’t seem to be taking their place with the same zeal. And even if they did, it wouldn’t be enough to shut down the more sophisticated BNP machine of today, a party that took 800,000 votes at the last European elections, dwarfing past totals. It would take a whole shift in the political discourse of the country into both a more leftward AND more working-class oriented direction for the BNP to go away, which ain’t happening anytime soon.

A sickeningly evil presence founded on the very worst political traditions of the twentieth century is growing in this country. No Retreat is a bold account of people who got off their arses and did something about it. Methods may need to change, but the same attitude is needed, now more than ever.

spikemagazine.com